(… Art theft and looting)

Count Julien de Rochechouart, the French minister’s memoir of his 1867 trip to Iran:*

‘The most beautiful enamelled bricks that have been made in Persia are those which decorate the mosque of Natanz.’

My city experienced a wide-scale looting following European’s interest in its art.

In medieval Persia potters in Kashan ( کاشان), 60 Km from Natanz developed ‘glittery metallic surface’ or ‘lustre painting’; a technique that applies compounds of metal oxides over a previously fired glaze before refiring *

As a result, in Iran of 13th and 14th century (then Persia), decoration of palaces and shrines flourished with glazed ceramic as never before.*

For centuries, these decorated tiles adorned both the interior and exterior of many buildings.*

Nonetheless, about 150 years ago organized pillaging seems begun in Iran when European travellers may have first drawn their attention to the splendour of Persian tile decoration.*

The earliest well-documented registers of Persian tiles from the V&A Museum and other sources indicate that thousands of tiles from various shrines were plundered in two phases.*

1st phase: 1862 to 1875, in cities of نطنز Natanz, ورامین Varamin, and قم Qum.*

2nd phase: 1881 to 1900, in cities of قم Qum, دامغان Damghan, and کاشان Kashan.*

‘Abd Al-Samad naked tomb in Natanz is the victim of over one hundred years of looting.”1

(MIT’s Archnet)

As a result, this is what is left in Abd-alsamad shrine in my city.

The pillage in Natanz: Tiles of امامزاده عبد الصمد Abd Al-Samad in Natanz have been removed, leaving only plaster with impressions of tiles..4 (Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In his Memoir, Rochechouart, the French minister confesses that he possesses some tiles from Natanz.*

According to Rochechouart’s description, the tiles were decorated with arabesques, flowers, leaves, and birds, and they bear “Persian” inscriptions.2

It is now widely acknowledged that they came from Natanz shrine, whose tiles decorated the shrine about 1308.3

Star and cross tiles (source: Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York)

Rochechouart’s memoir indicates that in 1862-63 the tile decoration in Natanz was sufficiently intact for him to admire its incomparable beauty (except for some missing).*

Jane Dieulafoy’s La Perse

Probably Rochechouart’s trip to Iran marks the very beginning of the Europeans’ acquisition of the Ilkhanid tiles.*

Nataz’s shrine and its looted arts re-appearing in European cities

The inter-locked stars & cross lustre tiles that once decorated the walls of Varamin’s shrine are also dispersed across the globe.*

The interest in Natanz’s tiles must already have been great in England by the time V&A Museum (then South Kensington) acquired a large group of Persian objects in 1876 .*

The illicit and systematic removal of a sizeable amount of lustre tiles across cities (soon re-appearing in Europe) involved an entangled web of actors and complicity.*

1967, London The V&A’s first exhibition (Smith’s collection): 3,517 objects, including 1,164 tiles. Tiles formed roughly one-third of the entire acquisition.7

A much wider scale pillaging of the palaces and shrines also continued in other cities; Varamin (ورامین) , Qom (قم), Kashan(کاشان), Takht-e-Soleiman (تخت سلیمان) …

City of Varamin (Imamzada Yahya , ورامین- امامزاده یحیی)

Varamin was the capital of ری Rayy province from 1260 to 1310.*

Varamin shrine was another plundered site for its lustre painting star and cross tiles with stylized vegetal decoration and Qur’anic inscriptions.*

The higher structure of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin remains intact

But its inter-locked stars & cross lustre tiles that once decorated the walls of Varamin’s shrine are also dispersed across the globe.*

The missing mihrab today

While thousands of these tiles are displayed at museums and private collection worldwide, it is not surprising that relevant information is missing because tiles must have been secretly removed from buildings by plunderers.

Some tiles, bearing dates ranging from December 1262, are now in cities as Chicago, Doha, St. Petersburg, Tbilisi, London, Oxford, Paris, Glasgow, Baltimore, Los Angeles, Honolulu, Tokyo.*

Tiles of Varamin shrine- Art Institute of Chicago

The Varamin shrine’s 12ft tall mihrab has sixty tiles with distinct sets of Quranic inscriptions. It is signed by ʿعلی بن محمد بن ابی طاهر’ ‘Ali b. Muhammad b. Abi Tahir’ in May 1265.*

Mihrab points to the praying direction.is a central part of a mosque,

Varamin’s mihrab is now in Shangri La, Honolulu, home of the American collector Doris Duke.*

Another one, signed by ‘یوسف بن علی بن محمد بن ابی طا’هر’ ‘Yusuf b. Ali b. Muhammad b. Abi Tahir’ is now kept in the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.15

But how was such a wide-scale looting organised?

In growing concerns about the stripping of tilework from sacred sites. in 1876 Iranian government (Qajar) had issued a decree protecting religious buildings. 18

Nonetheless, plundering continued after the decree.*

The illicit and systematic removal of a sizeable amount of lustre tiles across cities (soon re-appearing in Europe) involved an entangled web of actors and complicity.*

Some pieces were smaller interlocked stars while others were large (e.g. mihrabs).*

This difficult, and laborious process entailed the deconstruction of vast walls and surfaces piece by piece, large or small.*

‘Villagers said that Farangi (فرنگی ها or Europeans) gave them several tomans (Iranian currency) to remove some of the tiles.22

(E.G. Browne)

In the case of V&A Museum (then South Kensington Museum), the museum commissioned an agent to collect and transport museum-quality ancient artefacts.*

The agent was Major General Rupert Murdoch Smith who was working in Iran as the Director of the British Telegraph (Indo-European Telegram Department). 6

He said that he was told that a three-piece lustre panel that once covered a cenotaph (comparable to the panel in Hermitage) had been “hidden underground until an opportunity of smuggling it into Tehran could be found.”24

Before his director role in the Indo-European Telegraph Department in Iran, Smith was involved in excavation and transporting ancient statues and other artefacts from Turkey, Egypt and Malta for the British Museum.

In his mission in Persia he transported the large collections of artefacts through Iranian port of Busher and Suez Canal. ‘For insurance purposes in arranging the transport of one collection, along with the religious tiles from Qum, Smith valued it at £3100. ‘30

In one shipment, the value of the art collections was larger than the cost of the first underwater telegraph to connect Britain to France in 1850. The cable laid across the 32 km English Channel by Jacob and John Brett for £2,000.*

That collection travelled over 1000 km by mule train for 45 days from Tehran to Busher port in the Persian Gulf. An order from an Iranian official سپهسالار اعظم had come that it not to be opened, inspected, or taxed while en route.31

However, the caravan was stopped and inspected at each appropriate stop by the British Telegraph officials who wired news of its progress to Murdoch Smith. 32

Smith instructed the shippers, Gary, Paul and Company to transit it by way of the Suez Canal rather than through Bombay. 32

Moya Carey’s of the V&A Museum refers to these items as “sensitive acquisition.”22

Being aware of the 1876 protection of the religious site law in Iran (then Persia), Smith said ‘impossible’ when declined to provide photographs of the original buildings.”23

Murdoch Smith’s network had many collaborators.

Among many was Jules Richard, a Frenchman who arrived in Iran (then Persia) in 1944, almost a decade earlier than Smith as a photographer. He was also the French language instructor at دارالفنون ‘Dar al Funan’, the first European school in Tehran.

He became Muslim. He was also the Qajar court’s photographer.

Another collaborator was Jean-Baptiste Nicolas, who arrived in Iran three years earlier than Smith as the secretary to the French legation in Tehran.*

Sidney Churchill, Smith’s employee at the Tehran office of the British Telegraph (Indo-European Telegraph), was also in his network9

Three of the remaining mihrabs are now in موزه استان قدس Astan Ghods Museum in Mashhad, Iran and another mihrab is in Tehran’s Islamic Museum.25

Share the story

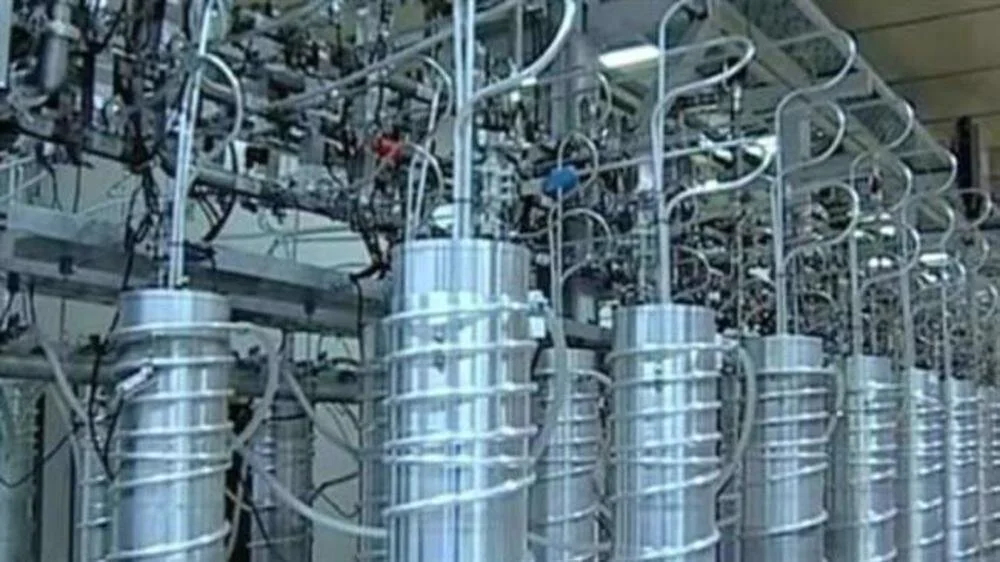

Beyond Its Nuclear Facility; my city Natanz

Tweet

Special thanks to Tomoko Masuya, Keelan Overton, Kimia Maleki, and Leonard Helfgott and the V&A Museum for contributing to the main body of this adaptation. Sentences showing an asterisk (*) above may be traced to the provided research materials containing over 110 Parsian and English academic references.

Suggested reading materials and references:

- The Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin: A Present History of a Living Shrine, 2018–20, Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World, Authors: Keelan Overton and Kimia Maleki

- Carpet Collecting in Iran, 1873-1883: Robert Murdoch Smith and the Formation of the Modern Persian Carpet Industry, Author(s): Leonard Helfgott, Source: Muqarnas , 1990, Vol. 7 (1990), pp. 171-181,

- Persian Tiles on European Walls: Collecting Ilkhanid Tiles in Nineteenth-Century Europe, Author(s): Tomoko Masuya, Ars Orientalis , 2000, Vol. 30, Exhibiting the Middle East: Collections and, Perceptions of Islamic Art (2000), Published by: Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan

- Obituary: Major-General Sir R. Murdoch Smith, R. E., K. C. M. G. Author(s): Frederic J. Goldsmid Source: The Geographical Journal , Aug., 1900, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Aug., 1900), pp. 237-238

One thought on “Beyond its nuclear facility, my city Natanz”

Comments are closed.